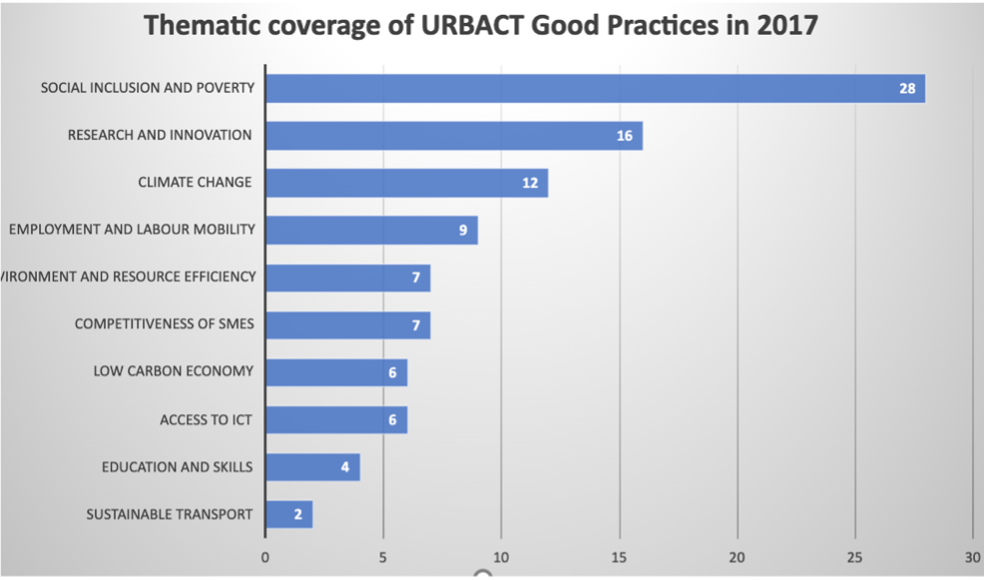

As part of our Good Practice campaign, we investigated in a previous article what makes an URBACT Good Practice ‘good’. Two distinguishing features are ‘local impact’ and ‘transferability’, which can take many forms and contexts – as evident in the 97 URBACT Good Practices awarded in 2017.

This article focuses on one practice in particular and its transferability and local impact: the Playful Paradigm. Find out how one city in Ireland adapted an URBACT Good Practice, developed by an Italian city, and transferred it at a national level. Your city could experience similar benefits if you send us your good practice!

Defining ‘transfer’ in the URBACT programme

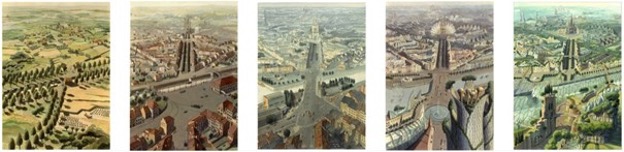

In the context of the URBACT programme, a ‘good practice’ can be transferred through a specific model of ‘understand-adapt-reuse' supported by transfer networks. In the Playful Paradigm Transfer Network, as Lead Partner, Udine found a way to make the city landscape playful, officially recognised as an URBACT Good Practice. Awarded by URBACT in 2017, Udine’s experience with modes of play provided a template for not only reanimating underused, car-dominated public spaces but also to improve social inclusion and initiate community-led placemaking.

Through the URBACT Playful Paradigm Transfer Network, Cork (IE) developed a host of play actions in line with Udine's Playful Paradigm practice. “We went for something that was very pioneering in terms of trying to create a ‘playful city’…what does this actually mean?”, explains Kieran McCarthy, Lord Mayor of Cork (2023-2024) and an independent member of Cork City Council. ‘It’s really about re-thinking how we use our public spaces: closing off streets and creating playful areas’.

Cork was inspired by the Udine example to develop a variety of play actions, including:

- The re-pedestrianisation of the Marina walkway, a historic walkway dating back to the 19th century.

- Getting permission to temporarily open streets for play (for example every Sunday for a month).

- Promoting the concept of Play Streets which at its core is the repurposing of the street for free play (setting up tug-of-war stations and big Connect 4 stations).

- Playful Cultural Trail of cultural institutions (including museums, art galleries, community centres, etc.).

According to Lord Mayor McCarthy, “These spaces were playful areas in the past, so it’s great to see families engage and discover these streets, their origins, and even their own neighbours.” As a transfer partner city, Cork also embraced the power of the practice (of play) to address other urban challenges (e.g. public health, environment, place-making, etc.). For instance, play packs and place-making training helped to reduce social isolation of Cork’s elderly population during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cork’s application of the URBACT Good Practice proved its transferability, not only to other European cities but cascaded at national level.

Continuing the transfer from European to national scale

Starting in 2021, the Cork URBACT Local Group spearheaded URBACT’s National Practice Transfer Initiative (NPTI) in Ireland – one of five intra-country transfer pilots reinforcing best practice exchange and URBACT’s added value in different European countries. With the support of the Irish National URBACT Point and a national URBACT expert, Cork helped to transfer the Playful Paradigm practice in 5 Irish towns: Donegal, Portlaoise, Rush, Rathdrum and Sligo. “The different groups and town representatives came to Cork”, remembers Lord Mayor McCarthy. “I had the chance to speak to them about the impact of URBACT, and why they should engage with the URBACT programme.”

Inspired by the Cork example, the five Irish partners got to work imagining how they could make it work in their own municipalities. The partner towns developed and implemented transfer plans, involving a variety of actions based on Cork’s experience with the Playful Paradigm. These plans were different, depending on the local context, but all focused on liberating streets and public places to the public – not just children, but all generations and groups.

In Donegal, for instance, the Diamond town square was turned into play areas, and residents young and old were invited to have fun and connect with each other. Just north of Dublin, in Rush, the URBACT Local Group (ULG) created a Play Street. An area typically occupied by cars, this space became ‘open for play’. The Rush ULG members also created a storytelling trail involving the local library and community centre. Local community organisations in Portlaoise prioritised involving disadvantaged or vulnerable communities; in particular, the town got the Ukrainian refugee community involved. Sligo reanimated its town centre with new pedestrian sidewalks and cycle lanes as well as improvements to benches and street furniture. Play events, where busy retail streets in the centre were temporarily closed for car traffic, were well received by residents and businesses alike. Some of the successful elements that Sligo decided to implement following the Cork visit included installing the first parklet in the town (taking out two parking spaces and creating a seating area where residents and visitors can meet and linger) as well as a space for colouring chalk on the street. They are now partner in a new European network called Cities@Heart, to create a healthy and harmonious heart of the city.

In a quirky turn of events, different communities decided to use recycled materials to play. Deep in the woods of Rathdrum, locals took part in ‘snowball fights’. Instead of waiting for snow, old (washed) socks were used to kick off play activities. The town’s new library provided a perfect location to adapt a variety of play actions, including a book loaning system. This system has been expanded to all libraries in County Wicklow.

Exceeding expectations: making play a priority in Irish towns

Throughout the URBACT National Practice Transfer Initiative, Cork was able to delve deeper into its own recognised playful practice based on engagement with Udine and other European partner cities. Cork also took a hands-on role in offering material support and guidance to the partner municipalities (e.g. a manual for incorporating playfulness, Let’s Play Cork brand guidelines, etc.)

Looking closer at the impact of the national transfer, it is clear that the learning exchange went both ways between the Lead Partner and partner cities.

Irish partners answer Cork’s call to action

Feedback has been positive across the local partners, according to Wessel Badenhorst, the URBACT Lead Expert who accompanied the transfer process. Partners in the five transfer towns and cities brought fresh perspectives to the conversation with Cork on the Playful Paradigm, pushing the boundaries of what playful spaces, events and engagements could look like in a specifically local, Irish setting.

“It is worth noting that all partners in the Ireland transfer initiative reported that the impacts of their play activities and interventions exceeded their expectations,” stated Wessel. The most telling endorsements were that residents are requesting more play activities and that funding for play activities are being secured from national and municipal sources. All partners implemented their transfer plans, hence proving the value of the adapted and re-used actions first observed in Cork (the transfer city). And, although most people instinctively know that play makes everyone feel better, the national initiative helped the partner towns to observe and understand how, over time, the opportunities for free play in Irish towns have been reduced for example by allocating too much space for the exclusive use of cars. With practical low-cost play activities, the partner towns demonstrated to their residents that a more liveable alternative is possible.

Cork finds its playful calling

According to Martha Halbert, Social Inclusion Specialist in Cork City Council: “Showcasing the work to our colleagues across cities and towns in Ireland represented not only a unique network building exercise for local government colleagues, but it encouraged us to look at the local factors which made the work unique and transferable.” Lord Mayor McCarthy can attest to this: “I’ve seen the joy my team gets from telling the story of Cork and the Playful Paradigm.”

In addition to the types of connections and exchanges, the national transfer component has also helped to boost staff training: not just keeping staff skill sets up to par but also informing them of developments in the playful paradigm in the EU context.

Stepping back even further, the URBACT Playful Paradigm kick-started Cork’s investment in restoring public spaces as ‘playful places’. They secured Healthy Ireland funding to employ a Play Coordinator for Cork City, who is dedicated to increasing the profile and value of play in communities as well as at strategic policy level. Martha adds, “Play learnings are firmly embedded in the policy and structural landscape in Cork City now”. It also provided a stepping-stone for the city to get involved in other EU-level initiatives such as Horizon projects, and the EU Mission for Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities, of which Cork is one of the 112 selected laureates.

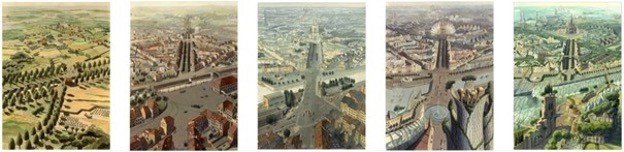

Children playing in activities of the Playful Paradigm initiative.

URBACT’s call for Good Practices: Cork’s advice

URBACT has a legacy of recognising specific methods, approaches and tools for making cities green, just and productive. These URBACT Good Practices are part of a legacy of positive change, not just at European but also at national and local levels.

"My call to any local government is to submit your good practice!” encourages Lord Mayor McCarthy. “Some of the world’s largest challenges exist in urban areas, and every municipality across the European Union is working on some important nugget that can help other cities and towns. Don’t leave it to others to write up the good practices!”

We hope that Cork’s experience inspires you to share your good practice.

Interested in applying to the new URBACT Call for Good Practices (open until 30 July 2024)?

All you need to know can be found on urbact.eu/get-involved.